Policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy tied to worse birth outcomes

New study suggests even “supportive” policies lead women to delay or avoid prenatal care

Emeryville, CA (June 18, 2018) – A majority of state-level policies targeting women’s alcohol consumption during pregnancy—even policies designed to support pregnant women—lead to more adverse birth outcomes and less prenatal care utilization, according to a new study from ARG and Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH), a program at the University of California, San Francisco, published today in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research.

Six policies were significantly associated with poorer birth outcomes, including low birthweight, premature birth, and a low APGAR score:

Six policies were significantly associated with poorer birth outcomes, including low birthweight, premature birth, and a low APGAR score:

- Policies requiring warning signs in locations where alcoholic beverages are sold (Mandatory Warning Signs)

- Laws addressing the legal significance of a woman’s conduct prior to birth of a child and damage caused in utero and, in some cases, defining alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse or neglect (Legal Significance for Child Abuse/Child Neglect)

- Policies requiring involuntary commitment of a pregnant woman to either treatment or protective custody (Civil Commitment)

- Policies that prohibit the use of medical test results as evidence in the criminal prosecutions of women who may have caused harm to a fetus or a child (Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution)

- Mandatory or discretionary reporting of alcohol use or abuse by women during pregnancy for data gathering purposes or provision of health services (Reporting Requirements for Data and Treatment Purposes)

- Policies giving pregnant women who abuse alcohol priority access to substance abuse treatment (Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women)

“It is likely that women who drink during pregnancy in states with these policies may be avoiding prenatal care out of fear that they will discover their use has already irreversibly damaged their baby, or out of fear that they will be reported to Child Protective Services and either lose their children or go to jail,” said senior author Sarah CM Roberts, DrPH, Associate Professor at ANSIRH at the University of California, San Francisco.

“Presumably these policies are intended to improve birth outcomes and longer-term child well-being, but our study suggests that regardless of whether these policies are designed to be supportive or punitive, at best they do nothing, and at worst they cause measurable harm,” said lead author and ARG biostatistician Meenakshi Sabina Subbaraman, Ph.D.

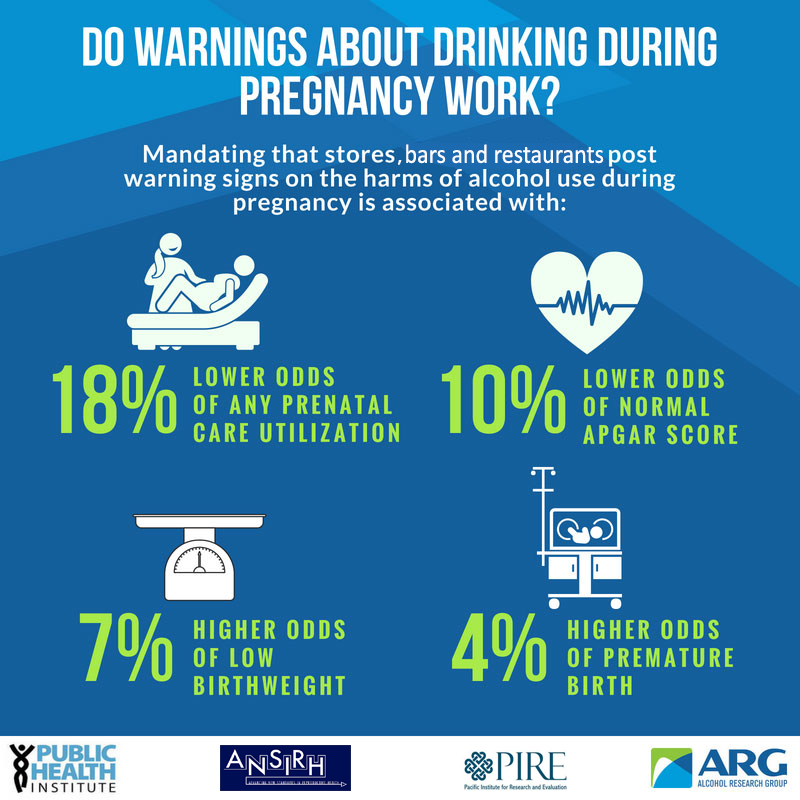

The policy of requiring mandatory warning signs was related to the most outcomes. Living in a state with the policy was related to 7% higher odds of low birthweight, 4% higher odds of premature birth, 18% lower odds of any prenatal care utilization (PCU), 12% higher odds of late PCU, and 10% lower odds of a normal APGAR score.

On the other hand, alcohol policies that target the general population—retail control of wine sales and any other policies that lead to decreased population-level consumption—were associated with improved birth outcomes.

“Regulations aimed at reducing alcohol use in pregnancy have spread across the nation since the 1970s, yet there has been little research on the impacts they are having,” said Subbaraman. “If the policies are leading women who drink to avoid prenatal care, healthcare providers are missing opportunities to not only support healthy pregnancies, but to promote interventions that help women reduce or stop drinking.”

The study used birth certificate data from a large general population sample of over 148 million live births across all 50 states between 1972 and 2013, examining the relationship between eight state-level policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy and birth outcomes.

This is the first study to date examining whether policies regarding alcohol use during pregnancy are related to adverse birth outcomes. States began enacting policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy in 1974, shortly after the first clinical reports of fetal alcohol syndrome in the modern era. Almost all states have enacted either supportive or punitive policies since then. Mandatory warning signs and reporting requirements for treatment and data purposes were the most common policies in 2016.

Two other policies examined in the study—reporting requirements for child protective services and regulations guaranteeing priority treatment for pregnant women and women with children—were not significantly related to any outcomes.

###

Subbaraman, M.S. Thomas, S., Treffers, R., Delucchi, K., Kerr, W.C., Martinez, P., Roberts, S.C.M. (June 2018). Associations between state-level policies regarding alcohol use among pregnant women, adverse birth outcomes, and prenatal care utilization: Results from 1972-2013 Vital Statistics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/acer.13804

Research reported in this press release was supported by the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AA023267 (S.C.M. Roberts). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

If you are interested in arranging an interview with Meenakshi Sabina Subbaraman, Ph.D., contact Diane Schmidt at (510) 898-5819 or dschmidt@arg.org. If you are interested in arranging an interview with Sarah CM Roberts, DrPH, contact Jason Harless at (510) 986-8963 or harless.jason@ucsf.edu.